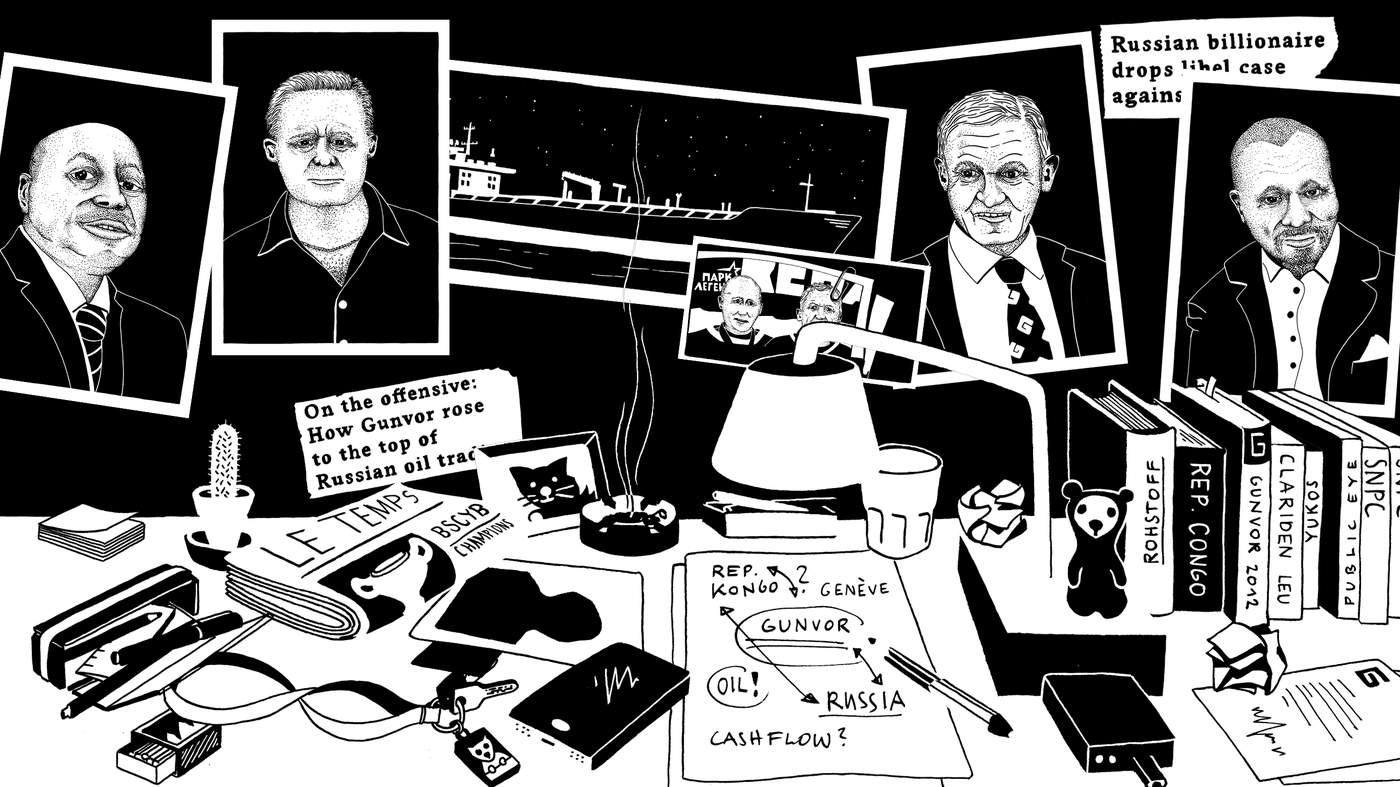

In January 2012, the offices of Gunvor in Geneva were searched. Nothing, or almost nothing became known about the criminal investigation, but Public Eye dived right into the twists and turns of this tentacular affair.

On 3 July 2012, Gunvor took centre stage on French-speaking Swiss television. RTS broadcast a programme during a primetime evening slot relating to an event that occurred in Geneva in January of that year. Federal Police had raided the offices of Gunvor, the world’s fourth largest oil trader. The criminal prosecution authorities set their sights on suspicious payments connected to oil deals between Gunvor and the opaque Société nationale des pétroles congolais (SNPC), which markets the black gold on behalf of the Congolese state. They suspected money laundering operations had taken place. Gunvor would surely have preferred not to have to face that kind of attention.

19h30 - RTS, 3rd July 2012.

Did Gunvor pay bribes to access the much sought-after Congolese black gold market? Or was it a case, as claimed by the company, of a «crooked employee» who had allegedly transferred millions without his superiors knowing anything about it? The investigation of the Office of the Attorney General of Switzerland is still ongoing.

In early 2016, we decided to look into the case. Not an easy task, in a branch were secrecy rules supreme. Over the course of 18 months, we spoke to dozens of sources - most of whom asked to remain anonymous. We painstakingly went through the trading data, traced the course of tankers and estimated the profits…

Here are the findings of our investigation.

With this dynamic duo, all the links in the Congo chain were in place. The only thing left to do was to find a way to persuade the presidential family to sell its oil to Gunvor. The trader then played two trumps… and won the hand!

Gunvor played two trumps to win the hand. One was geopolitical, the other financial. The former involved a promise to play matchmaker between the Congolese and Russian governments. At the time when the Geneva-based company was publicly denying any connection with the Kremlin and showed an uncompromising attitude towards the media every time they brought up the close relationship between Timchenko and Putin as the key to its success, Gunvor's representatives were using this very same argument to persuade the Congolese authorities to agree to enter into dealings with them.

According to two of our sources, Gunvor had allegedly promised the Congolese that by aligning themselves with a «structure controlled by Putin», they would see «the doors to Russia’s economic cooperation agreements open» in front of their eyes. The Kremlin also pledged to defend the Congo in UN bodies. Piecing together different bits of information, we learnt that Timchenko then flew the son of the Congolese president to Moscow in his private jet. This was in 2010. During his «tour of the great dukes», «Kiki» met the Russian energy minister as well as the owners of Russia’s main oil groups. The aim of the visit: to prove to Congolese officials that Gunvor could access the highest spheres of Russian power.

And Gunvor was not bluffing. On 31 August 2011, the Russian and Congolese governments signed an economic cooperation agreement focused on the energy sector. Russia committed to support any companies investing in Congo’s oil.

Gunvor had a second ace up its sleeve: finance.

Unlike the Republic of Congo, which is notoriously corrupt and indebted, the Swiss trader enjoyed easy access to credit from major banks active in trade finance. The Congo needed fresh money? No problem for Gunvor. It quickly found a bank that would lend some of the capital which Gunvor then lent to Brazzaville: BNP Paribas.

The group subsequently offered to the Congolese authorities a loan pledged on oil, a form of mortgage on future deliveries of black gold. In jargon, this is a «pre-financing» deal or a «prepayment». And so, Gunvor became the «Bank of Congo», without, however, being subject to the regulations applicable to financial institutions.

Gunvor's strategy would soon pay off. In June 2010, «Kiki» signed an agreement with the Geneva-based trader for three shipments of crude oil. But the main course came in January 2011 in the form of a second contract which lead over the following months to the lifting of an additional 19 tankers, each worth some USD 100 million.

All in all, Gunvor lifted 22 shipments of crude oil between 2010 and 2012, the total value of which came to about USD 2.2 billion.

None of these deals went through a tender process, contrary to the provisions of the Congolese Code of Public Procurement. They were therefore illegal under Congolese law. Asked for comment by Public Eye, Gunvor declined to comment. For his part, «Kiki» simply stated that Congo was «a sovereign state that has the legal standing to choose who it does business with. This was done transparently and legally.»

Géraldine Viret, spokesperson for Public Eye, looked at Gunvor's communication strategy.

Conversely, Pascal C., the former Gunvor employee retorted in March 2013, by filing a lawsuit against Gunvor for «false allegations». According to our information, in the spring of 2017, Pascal C. admitted to the judge to having been actively involved in paying commissions which he knew were meant for foreign officials – in particular President Sassou Nguesso’s clan. He claimed to have acted in his capacity as employee and to have done so with his superiors’ knowledge.

What happened next seems to confirm that Pascal C. was not the only one involved.

Shaken by these legal troubles, Gunvor did not give up the fight. The company tried to restart its business in Congo, no matter what the cost.

Who at Gunvor knew about the suspicious payments? While the justice system was trying to clarify what actually happened, the Geneva-based trader was in no way admitting defeat. On the contrary, the company decided to crank up the pace and did not hesitate to take unprecedented risks to revive its business in Congo. In July 2012, it signed a contract with Yoann Gandzion, the son, whose accounts had been blocked by Swiss authorities on grounds of suspicious transfers. Gunvor then enlisted the services of another one of its «African» intermediaries. The man chosen this time was Oliver Bazin, nicknamed «Colonel Mario», an even dodgier character.

In 2014, Gunvor was on the verge of regaining control of Congolese oil, but events took an unexpected turn.

In June 2014, the lawyers of Pascal C. and Jean-Marc Henry contacted Gunvor, claiming to be in possession of damning footage that was clear proof of the trader's corrupt practices in Africa. The lawyers put a deal on the table: the recording would not see the light of day if Gunvor withdrew the complaints against their clients. But, receiving no reply from the firm, they handed everything over to the prosecutor in charge of the case.

Public Eye was able to see the infamous footage with its own eye.

«In that way we will be able to buy off anyone and that is how we will be able to settle all the expenses related to the tankers. This is also the message we would like to convey to Denis Christel.» – damning footage extracts.

For the lawyers of Jean-Marc Henry and Pascal C., this video unequivocally showed that the proposal was to set up a structure that would make payments to Congolese officials. The prosecutor seems to be of the same opinion. He brought an action against Bertrand G. for «bribery of foreign public officials». The prosecutor also heard Bazin who, according to our information, is no longer working for Gunvor today. In addition, the oil contract signed in Congo in 2014 has been cancelled.

Bertrand G. was dismissed by Gunvor in September 2014. As far as we know, he signed a document acknowledging that he had acted on his own initiative in meeting with «André» and Olivier Bazin, and not on the instructions of his employer. Do we still think it is acase of a «crooked employee»? According to one of our sources, in exchange for signing this document, and to pay for his silence, Gunvor allegedly shelled out USD 700,000. Bertrand G. has apparently since decided to leave the oil industry. Gunvor’s Africa Desk is no longer based in Geneva, but in Dubai – far from the Swiss justice system, which continues to lead its investigation.

What lessons can we draw from this story?

As host country for some 500 companies active in the commodities sector, including the world's major players, Switzerland must assume its responsibilities. Although the Federal Council has recognised since 2013 the «reputational risk» that this sector poses to Switzerland, it continues to rely solely on the good will of the firms, expecting them to «conduct themselves responsibly, and with integrity». This goes to show just how the attitude of the Swiss federal authorities is at best verging on naivety and at worst on complacency or cynicism.

Gunvor’s adventures in Congo show us once more the need for regulation of the trading sector.

Andreas Missbach, Head of Commodities and a member of the Governing Board at Public Eye, explains why Switzerland should take action.

Shining a light where nefarious people prefer their activities to remain hidden in the shadows, denouncing harmful actions and proposing specific solutions: these are Public Eye's aims.

Through research, advocacy and campaigning, we are fighting injustices that have a significant link to Switzerland and making the voice of our 25,000 members heard for a responsible Switzerland.